Bangladesh's two decades: Out of the basket into the Future

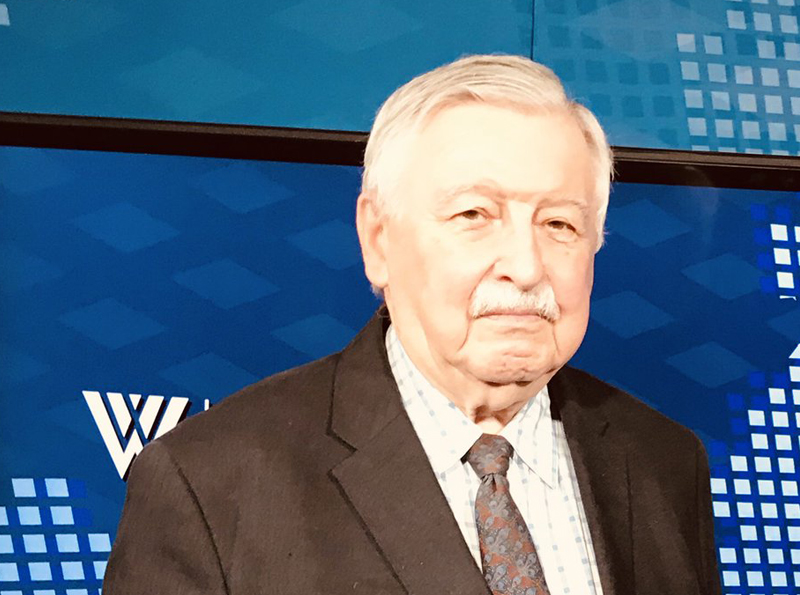

William Milam

Prothom Alo has asked me to help mark its 12th anniversary by contributing a short essay on how I view the last two decades in Bangladesh, from the time I came to know the country well, to the present. During these two decades, of course, one of the more impressive successes in Bangladesh has been Prothom Alo itself.

Its phenomenal growth in those 12 years has led to a general maturing and sharpening of the press in the country and contributed mightily to a much better informed public, and an electorate that is primed and prepared for a deepening of democracy and public service accountability. I commence this essay by offering my sincere and profound congratulations to Prothom Alo for helping to create some of the conditions I will write about below.

I don’t believe that Bangladesh was ever a “basket case.” But when I arrived in Dhaka in August 1990 it was a different city in many ways than it is today, and Bangladesh was a country that seemed to have lost its political direction. It was my good luck to arrive at a time when great change was just over the horizon, and to be witness to a political breakthrough that should have resonated throughout the third world.

I presented my credentials to a president named Ershad. As chief of Staff of the Bangladesh Army, General Ershad had seized power from a democratically elected government 8 years earlier. He had spent most of the time since trying to find political legitimacy, using the government to curry favour with interest groups, playing on the hostility between the two main political parties to keep the opposition divided, and even shedding his uniform and becoming a civilian politician with his own political party. But by mid-year 1990, time was running out on Ershad, as it had, or would, in those years on an array of non-democratic regimes around the world.

By 1990, democracy seemed to be breaking out all over. The Philippines led the march in 1985. Pakistan’s military dictator died in 1988 and was succeeded by a democratically elected government. The Berlin Wall came down in 1989, and the Soviet Empire in Eastern Europe broke apart like a shattered glass. A year later the Soviet Union, itself, came tumbling down. Everywhere, autocracy seemed to be on the way out, and democracy on the way in. Democracy was “The End of History” wrote the scholar Francis Fukuyama, an automatic outcome of the dynamic forces of history that were coming together in the late 20th century.

Certainly Bangladesh would join that parade. And it did so, with a typically Bangladeshi twist on the usual pattern. In the summer of 1990, the political parties (except for Ershad’s) stopped their quarrelling for a change and launched a movement against Ershad that soon had him and his government on the ropes.

They agreed on a two point agenda: 1) Ershad must go; and 2) a neutral caretaker government led by a respected and neutral president would oversee a free and fair election. The concept of a neutral caretaker government to oversee an election was one of the unique aspects of the Bangladesh democratic revolution. It is, to my knowledge, the only country in which that concept has been incorporated into the constitution.

A second unique aspect was that that Ershad, a former army leader who had based his claim to power on the support of the army, fell quickly and without much bloodshed because the army refused to back him when he called on it to do so. The army didn’t just eschew power (which armies elsewhere had done before, and have done since), but it refused to use force against its fellow citizens to save its former commander.

In a sense, the Bangladesh army has followed this path twice in the past two decades, once when it refused to intervene to save Ershad , and once, at the beginning of 2007, when it did intervene rather than face the prospect of either disobeying an order from its constitutional commander in chief or putting down with force the certain mass rising against a rigged election. (As we know, it gave up power on schedule, after two years.)

The elation we all felt in those halcyon days of late 1990 and early 1991was soon deflated as Bangladesh democracy in action soon proved that it takes more than hope, enthusiasm, and an army that doesn’t want to be involved in politics, to build a sustainable democracy. It takes history — a history of creating strong institutions that deepen with time and sustenance, institutions that provide a check on government power and accountability for its actions; an independent judiciary that is intent on protecting democratic structures and institutions is one example. It takes a culture of openness and tolerance that provides the give and take of democratic discourse and of compromise.

I have watched Bangladesh closely since, and with most of its foreign friends, have hoped in vain that the institutions and habits of mind that sustain real democracy would grow with the experience of democracy — in other words, that the political culture in a democratic setting would cleanse and reform itself. It has not.

Describing the political culture or explaining why it does not change is, I think, beyond my powers of articulation. Its essence is that it is characterised by an unadulterated drive for power, both for the parties in power, and those that are not, that overrides all the cultural inhibitions and formal constraints that temper life in a truly democratic structure. Nothing, not violence, not corruption, not cheating, not lying, is ruled out in the effort to retain or gain power. In political terms, Bangladesh has gone in circles since the election of 1991.

And the circles have, unfortunately, wound downward in an ever-tightening spiral. The nadir was reached in early 2007 when the sitting government’s intention to rig the upcoming election was so blatant that mass violence, and much bloodshed, was a certainty. Even that prospect did not deter the government from its plans.

The army intervened again after a 17-year hiatus to save lives and property, but promising political reform in a two-year period of military/technocratic rule. It kept to the time frame it promised. But reform was beyond its power — in two years or twenty. Now, almost two years after power was returned to civilian authority, the political circles are wider, but their direction is anything but linear. The best that can be said is that, politically, Bangladesh is back where it started almost 20 years ago.

I believe, however, that Bangladesh has the opportunity to be one of the success stories of the future because, while going in circles politically, it has set a course economically and socially that will lay the foundation for a straighter, and more democratic, political culture. It is no secret that, primarily through the diligent work of NGOs, Bangladesh has probably been more successful in overall human development than almost any other third world country, and certainly than any of the South Asian countries.

Bangladeshis have a right to be very proud of the progress the country has made in education, health, gender parity, literacy, and in the innovative programmes of the world-famous NGOs. Micro-credit originated in Bangladesh, and has spread around the world. Brac now operates programmes in almost every aspect of social development, and has taken its operations abroad to Pakistan and Afghanistan, and as far away as East and West Africa. There are hundreds more.

It is this spirit of independence and self-sufficiency that gives me confidence about Bangladesh’s future. In each of the last three decades, the Bangladesh economy has gained more and more strength as the private sector gains more and more confidence. Its gains derive totally from the private sector, although I have to give credit to a series of economic policy makers who saw a good thing and simply stayed out of its way.

As garment exports have grown and new export products have come to market, not only do the economy and the foreign trade balance benefit, but these industries employ millions of women, who become the primary income earners of their families. In the end, the enormous gains in female education and literacy, as well as in women’s employment and income, mark Bangladesh as special in the third world and certainly in South Asia. Surely, its empowered women are the key to its enhanced future.

It is this human infrastructure of educated, literate, healthy, ambitious, and energetic women and men that gives me hope of political progress that will, someday, match the socio-economic progress the country continues to make. In time, they will demand of their leaders better and more democratic governance. This is the real “Bangladesh Option” that other South Asians sometimes talk about with envy.

COURTESY: PROTHOM ALO